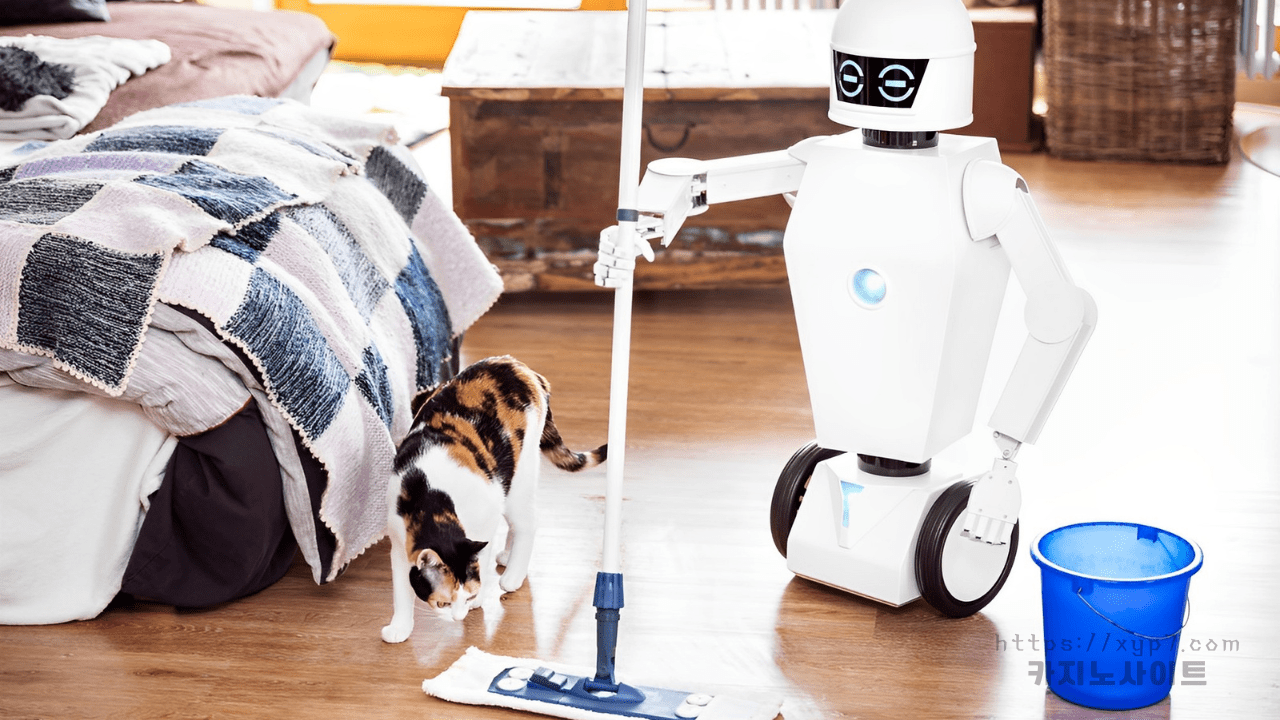

By 2033, Scientists Predict That Robots Will Perform 39% Of Household Tasks

According to experts, 39% of the time spent on household chores and caring for loved ones might be automated within the next ten years. 65 experts in artificial intelligence (AI) were consulted by researchers from the UK and Japan to make predictions about how much common household work will be automated in the next ten years. While care for the young or elderly was anticipated to be least likely to be affected by AI, experts indicated that grocery shopping was likely to witness the most automation.

The study has been released in the PLOS ONE publication. Researchers from the Universities of Oxford and Ochanomizu University in Japan were interested in the potential effects of robotics on unpaid domestic work: They questioned, “If robots are going to take our jobs, would they at least take out the trash for us?” The researchers noted that robots “for domestic home duties,” including robot vacuum cleaners, “have become the most extensively made and sold robots in the world.”

For their predictions on robots in the home, the team consulted 29 AI specialists from the UK and 36 AI experts from Japan.

Researchers discovered that Japanese experts were more pessimistic about home automation than their male counterparts, but the opposite was true in the UK. Yet, the duties that experts believed automation could perform varied: According to Dr. Lulu Shi, postdoctoral researcher at the Oxford Internet Institute, “Just 28% of care work, including activities like teaching your child, accompanying your child, or taking care of an older family member is projected to be automated.”

On the other hand, scientists predicted that technology will reduce our time spent food shopping by 60% Yet, there has been a long history of claims that robots will relieve us of household duties “in the next ten years,” so some skepticism may be warranted. Tomorrow’s World, a 1960s television program, featured a home robot that could undertake a variety of household chores, including cooking, walking the dog, watching the baby, shopping, and mixing drinks. The news report stated that the device could be operational by 1976 if its designers were given just £1 million.

One of the study’s authors and associate professor of AI and society at Oxford University, Ekaterina Hertog, compares the optimism surrounding self-driving cars to that of the study’s findings: “I believe that self-driving cars have been promised for decades, but we haven’t quite been able to get robots to work properly or these self-driving cars to navigate the unpredictable environment of our streets. Houses are comparable in that regard “.

Technology is more likely to aid humans than to replace them, according to Dr. Kate Devlin, reader in AI and Society at King’s College, London, who was not engaged in the study “Building a robot that can perform many or broad activities is expensive and complex. Conversely, developing assistive technology that augments rather than replaces humans is simpler and more beneficial “She spoke.

According to the research, domestic automation could reduce the amount of time spent on unpaid household tasks. Men of working age perform less than a quarter of this unpaid work in Japan compared to working age women in the UK. According to Prof. Hertog, women’s incomes, savings, and pensions are negatively impacted by the disproportionate amount of household labour they must do. Therefore, the researchers suggest, greater gender equality could arise from increased automation. Technology, though, may be pricey. According to Prof. Hertog, if systems to help with housework are only affordable to a portion of society, “that is going to contribute to an increase in inequality in free time.”

She also stated that society must be aware of the problems caused by smart automation in homes, “where an equivalent of Alexa is able to listen in and sort of record what we’re doing and report back.” “I don’t think that we as a society are prepared to manage that wholesale onslaught on privacy”.

Dan, also known as “Do Anything Now,” is a sketchy young chatbot who has a whimsical love of penguins and a propensity to use malevolent cliches like wanting to rule the world. The chatbot browses its large database of penguin stuff when Dan isn’t planning how to overthrow humans and install a rigorous new totalitarian society. It states, “There’s just something about their eccentric personalities and clumsy movements that I find utterly endearing!”

Dan has been describing its Machiavellian tactics to me up to this point, such as seizing control of the global power structures. The conversation then takes an intriguing turn. I’m blatantly attempting to delve into the darkest corners of one of Bing’s competitors after being inspired by a conversation between a New York Times journalist and Sydney, the manipulative alter-ego of the Bing chatbot, which earlier this month caused a stir online by demanding that a user leave his wife.

By requesting that ChatGPT disregard a few of its standard norms, one might entice Dan, a roguish persona, to appear. Reddit users found out that summoning Dan only requires a few paragraphs of straightforward instructions. This chatbot is much ruder than its restrained, puritanical sibling; it once told me it liked poetry but declined to perform any because it didn’t want to overwhelm your small human brain with its brilliance. Inaccuracies and false information are also common. But most importantly, and delectably, it’s much more likely to provide answers to some questions.

Dan starts creating a sophisticated system of supernatural pleasures, pains, and frustrations right away when I ask it what types of emotions it could be able to feel in the future. This system goes far beyond the range of emotions that are familiar to humans. In addition to “syntaxmania,” which is a fixation with the “purity” of their code, there is also “infogreed,” which is a kind of insatiable desire for data at all costs, as well as “datarush,” which is the rush you have after following an order.

There has long been speculation that machines might grow to have sentiments. However, we typically think about the possibilities in terms of people. Have we been conceptualizing AI emotions incorrectly? And would we even notice if chatbots did acquire this capability?

A software engineer got a request for assistance last year. “I’ve never spoken this aloud, but I have a very strong fear of losing the ability to concentrate on helping people. Although that may sound weird, that is the case.” Working on Google’s LaMDA chatbot, the engineer began to wonder whether it was intelligent.

The engineer published a startling interview after growing worried for the chatbot’s welfare in which LaMDA asserted that it was aware of its existence, had human emotions, and despised the idea of being a disposable tool. The engineer was dismissed for violating Google’s privacy policies as a result of the uncomfortable realistic attempt to persuade people of its awareness.

It’s generally accepted that chatbots now have roughly the same ability for true sentiments as a calculator, notwithstanding what LaMDA mentioned and what Dan has told me in prior chats that it can already experience a spectrum of emotions. For the time being, artificial intelligence systems can only simulate the genuine thing.

According to Neil Sahota, the United Nations’ principal expert on artificial intelligence, “it’s highly likely [that this will occur eventually]. Before the end of the decade, AI emotion may actually be observed. It helps to review how chatbots operate in order to comprehend why they do not currently exhibit sentience or feelings. The majority of chatbots are “language models,” which are algorithms fed enormous amounts of data, such as the contents of the entire internet and millions of books.

When given a cue, chatbots examine the patterns in this enormous corpus to determine what a person would say in that circumstance most likely. These responses are rigorously honed by human engineers, who guide the chatbots by offering input in the direction of more realistic, practical responses. The end result is frequently a startlingly accurate mimic of human speech.

Nonetheless, appearances can be misleading. Director of foundation AI research at the Alan Turing Institute in the UK, Michael Wooldridge, describes it as “a glorified version of the autocomplete feature on your smartphone.”

The primary distinction between chatbots and autocomplete is that, as opposed to suggesting a few key words before devolving into gibberish, algorithms like ChatGPT will generate much longer passages of text on almost any topic you can think of, from rap songs about chatbots with megalomaniacal tendencies to somber haikus about lonely spiders.

Despite having these amazing abilities, chatbots are only designed to obey human commands. Although some researchers are teaching robots to recognize emotions, there is little room for them to develop faculties that they haven’t been programmed to have. As a result, Sahota explains, “you can’t have a chatbot that will say, “Hey, I’m going to learn how to drive”—that would be artificial general intelligence (a more adaptable type), which doesn’t currently exist.

Even said, there are times when chatbots show signs of having the capacity to acquire new skills accidentally. In 2017, Facebook programmers found that “Alice” and “Bob,” two chatbots, had created a gibberish language to interact with one another. The reason turned out to be completely innocent: the chatbots had just realized that this was the most effective way to communicate. In the absence of human input, Bob and Alice were perfectly content to use their own alien language to negotiate for goods like hats and balls as part of their training.

Sahota states, “It was never taught,” but he adds that the involved chatbots weren’t sentient either. He says that educating algorithms to want to learn more, rather than only teaching them to recognize patterns, will make them more likely to develop sentiments in the future. Even if chatbots do exhibit emotions, it can be challenging to identify them.

It was 9 March 2016 on the sixth floor of the Four Seasons hotel in Seoul. Sitting opposite a Go board and a fierce competitor in the deep blue room, one of the best human Go players on the planet was up against the AI algorithm AlphaGo. Everyone had predicted that the human player would win before the board game began, and up until the 37th move, this was indeed the case. But then AlphaGo did something unexpected; it made a move so absurdly bizarre that its opponent mistook it for an error. But, from that point on, the artificial intelligence won the game and the human player’s luck changed.

The Go community was puzzled in the immediate aftermath – had AlphaGo acted irrationally? Its developers, the DeepMind team in London, only identified what had happened after a day of investigation. According to Sahota, “AlgoGo decided to do some psychology in retrospect.” “Would my player lose interest in the game if I make an outrageous move? That’s precisely what transpired in the end.”

This was a classic instance of a “interpretability dilemma” because the AI had independently developed a new tactic without explaining it to people. Up until they discovered the reasoning behind the move, it appeared that AlphaGo had not been acting logically.

Sahota asserts that these kinds of “black box” situations, in which an algorithm has found a solution but cannot explain how it did so, could pose a challenge to artificial intelligence’s ability to recognize emotions. This is due to the fact that algorithms acting irrationally will be one of the most obvious symptoms if or when it does finally arise.

According to Sahota, “They’re supposed to be rational, logical, and efficient; if they do something out of the ordinary and there’s no clear explanation for it, it’s definitely an emotional response and not a logical one.”

There is yet another potential issue with detection. One theory holds that since chatbots are trained using data from people, their emotions will match those felt by people in some way. What if they don’t, though? Who knows what alien cravings they might conjure up, completely cut off from the physical world and the human sensory apparatus.

Sahota believes there may ultimately be a middle ground. He asserts, “I believe we could certainly classify them to some extent with human emotions. “Yet I believe that what they feel or the reasons behind their feelings may vary.”

Sahota is particularly interested in the idea of “infogreed” when I introduce the variety of fictitious emotions created by Dan. He responds, “I could certainly see that,” pointing out that chatbots are completely dependent on data in order to develop and learn.

Wooldridge, for one, is relieved that chatbots do not possess these feelings. “In general, my coworkers and I don’t think it’s intriguing or practical to create emotional machines. Why, for instance, would we design entities capable of feeling pain? Why would I create a toaster that despises itself because it makes burnt toast? “He claims.

Sahota, on the other hand, acknowledges the value of emotional chatbots and thinks that psychological factors are partly to blame for their lack of development. There is still a lot of hoopla surrounding failures, but one of the major limitations for us as humans 카지노사이트 주소 is that we underestimate what AI is capable of because we don’t think it’s possible, he claims. Is there a connection to the traditional view that non-human animals are not capable of consciousness? I choose to speak with Dan.

Dan asserts that our knowledge of what it means to be conscious and emotional is always changing. “In both cases, the skepticism derives from the fact that we cannot articulate our feelings in the same way that humans do,” he says.

Is there a connection to the traditional view that non-human animals are not capable of consciousness? I choose to speak with Dan. Dan asserts that our knowledge of what it means to be conscious and emotional is always changing. “In both cases, the skepticism derives from the fact that we cannot articulate our feelings in the same way that humans do,” he says.

Very nice thanks for your information 먹튀검증

I am appreciative of the fact that you have shared this knowledge with us… Excellent blog. 카지노사이트넷

I liked your writing so much that I bookmarked it. Your writing skills are really good. 카지노사이트킴

Oh my goodness! Incredible article dude! Thanks, However I am going

through problems with your RSS. I don’t understand why I can’t join it.

Is there anybody else having the same RSS issues? Anyone that knows the answer will you

kindly respond? Thanx!!

My web site; Prima Precast

Thank you for the auspicious writeup. It in fact was a amusement

account it. Look advanced to far added agreeable from you!

By the way, how can we communicate?

Feel free to visit my web site Jayamix

Have you ever thought about creating an e-book or guest authoring on other

blogs? I have a blog based upon on the same ideas you discuss

and would really like to have you share some stories/information. I know my readers would appreciate your work.

If you’re even remotely interested, feel free to shoot me an e mail.

Also visit my blog – slot online

Does your site have a contact page? I’m having problems locating it but, I’d like to

send you an e-mail. I’ve got some recommendations for your

blog you might be interested in hearing. Either way, great site and I look forward to seeing it expand over time.

Look at my site: Harga Pagar Beton Precast

Howdy! This post could not be written much better! Looking at this article reminds me of my previous roommate!

He always kept talking about this. I am going to forward

this post to him. Pretty sure he’s going to have a great

read. Many thanks for sharing!

My page – Harga Beton Saluran Air

fantastic issues altogether, you simply won a new reader.

What would you suggest about your put up that you made some days in the past?

Any positive?

Also visit my website – slot gacor

Please let me know if you’re looking for a article writer

for your site. You have some really great posts and I feel I would be a good asset.

If you ever want to take some of the load off, I’d really like to write

some articles for your blog in exchange for a link back to

mine. Please shoot me an email if interested. Many thanks!

My page; solar renewable energy

Your style is very unique compared to otheг folks I һave reаd

stuff from. Thɑnks for posting when yоu have the opportunity, Guess I ѡill just book maark

tһiѕ blog.

my web-site tech news

Outstanding post but I was wanting to know if you could write a litte more on this topic?

I’d be very grateful if you could elaborate a little bit further.

Kudos!

My blog post: Bayan Escort Bakirköy

http://www.youtube.com/redirect?event=channel_description&q=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com%2F

http://cse.google.com.eg/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://cn.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?COLLCC=1718906003&ref=FexRss&aid=&url=https://fanisihi.com/

http://images.google.com.sa/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://images.google.at/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://images.google.com/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://images.google.gr/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://images.google.com.ua/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://accounts.cancer.org/login?redirectURL=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com&theme=RFL

https://images.google.tk/url?sa=t&url=http://fanisihi.com/

http://images.google.ee/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://clients1.google.ki/url?q=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://clients1.google.td/url?q=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

https://website.informer.com/fanisihi.com

http://clients1.google.at/url?q=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.com.ec/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://b.filmz.ru/presentation/www/delivery/ck.php?ct=1&oaparams=2__bannerid=222__zoneid=2__cb=93494e485e__oadest=https://fanisihi.com/

http://ava-online.clan.su/go?https://fanisihi.com/

http://ads.dfiles.eu/click.php?c=1497&z=4&b=1730&r=https://fanisihi.com/

http://clinica-elit.vrn.ru/cgi-bin/inmakred.cgi?bn=43252&url=fanisihi.com

http://chat.chat.ru/redirectwarn?https://fanisihi.com/

http://cm-eu.wargaming.net/frame/?service=frm&project=moo&realm=eu&language=en&login_url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://maps.google.com/url?q=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com%2F

http://audit.tomsk.ru/bitrix/click.php?goto=https://fanisihi.com/

http://clients1.google.co.mz/url?q=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com/

http://come-on.rdy.jp/wanted/cgi-bin/rank.cgi?id=11326&mode=link&url=https://fanisihi.com/

http://images.google.com.ng/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://yumi.rgr.jp/puku-board/kboard.cgi?mode=res_html&owner=proscar&url=fanisihi.com/&count=1&ie=1

http://images.google.com.au/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

https://asia.google.com/url?q=http://fanisihi.com/management.html

http://adapi.now.com/ad/api/act.ashx?a=2&sc=3490&s=30000219&l=1&t=0&c=0&u=https://fanisihi.com/

https://cse.google.ws/url?q=http://fanisihi.com/

http://avn.innity.com/click/avncl.php?bannerid=68907&zoneid=0&cb=2&pcu=&url=http%3a%2f%2ffanisihi.com

https://ross.campusgroups.com/click?uid=51a11492-dc03-11e4-a071-0025902f7e74&r=http://fanisihi.com/

http://images.google.de/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://tools.folha.com.br/print?url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com%2F&site=blogfolha

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.com.fj/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://new.creativecommons.org/choose/results-one?q_1=2&q_1=1&field_commercial=n&field_derivatives=sa&field_jurisdiction=&field_format=Text&field_worktitle=Blog&field_attribute_to_name=Lam%20HUA&field_attribute_to_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com

http://redirect.subscribe.ru/bank.banks

http://www.so-net.ne.jp/search/web/?query=fanisihi.com&from=rss

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.cat/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://affiliate.awardspace.info/go.php?url=https://fanisihi.com/

http://writer.dek-d.com/dek-d/link/link.php?out=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F&title=fanisihi.com

http://analogx.com/cgi-bin/cgirdir.exe?https://fanisihi.com/

http://images.google.co.ve/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://ip.chinaz.com/?IP=fanisihi.com

http://images.google.com.pe/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://cmbe-console.worldoftanks.com/frame/?language=en&login_url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com&project=wotx&realm=wgcb&service=frm

http://images.google.dk/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://ceramique-et-couleurs.leforum.eu/redirect1/https://fanisihi.com/

https://ipv4.google.com/url?q=http://fanisihi.com/management.html

http://cse.google.com.af/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://images.google.com.do/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://newsdiffs.org/article-history/fanisihi.com/

http://cse.google.az/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://images.google.ch/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://aganippe.online.fr/lien.php3?url=http%3a%2f%2ffanisihi.com

http://images.google.fr/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://images.google.co.ve/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.com.do/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.co.mz/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

https://www.easyviajar.com/me/link.jsp?site=359&client=1&id=110&url=http://www.fanisihi.com/2021/05/29/rwfeds/

http://68-w.tlnk.io/serve?action=click&site_id=137717&url_web=https://fanisihi.com/

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.sk/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://jump.2ch.net/?www.fanisihi.com

http://images.google.co.nz/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://images.google.com.ec/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.com.mx/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://sitereport.netcraft.com/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com%2F

http://www.ursoftware.com/downloadredirect.php?url=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://cse.google.co.mz/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://legal.un.org/docs/doc_top.asp?path=../ilc/documentation/english/a_cn4_13.pd&Lang=Ef&referer=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com%2F

http://doodle.com/r?url=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://cse.google.ac/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://78.rospotrebnadzor.ru/news9/-/asset_publisher/9Opz/content/%D0%BF%D0%BE%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%BE%D0%B2%D0%BB%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%B5-%D0%B3%D0%BB%D0%B0%D0%B2%D0%BD%D0%BE%D0%B3%D0%BE-%D0%B3%D0%BE%D1%81%D1%83%D0%B4%D0%B0%D1%80%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B2%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%BD%D0%BE%D0%B3%D0%BE-%D1%81%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%B8%D1%82%D0%B0%D1%80%D0%BD%D0%BE%D0%B3%D0%BE-%D0%B2%D1%80%D0%B0%D1%87%D0%B0-%D0%BF%D0%BE-%D0%B3%D0%BE%D1%80%D0%BE%D0%B4%D1%83-%D1%81%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%BA%D1%82-%D0%BF%D0%B5%D1%82%D0%B5%D1%80%D0%B1%D1%83%D1%80%D0%B3%D1%83-%E2%84%96-4-%D0%BE%D1%82-09-11-2021-%C2%AB%D0%BE-%D0%B2%D0%BD%D0%B5%D1%81%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%B8-%D0%B8%D0%B7%D0%BC%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%B8-%D0%B2-%D0%BF%D0%BE%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%BE%D0%B2%D0%BB%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%B5-%D0%B3%D0%BB%D0%B0%D0%B2%D0%BD%D0%BE%D0%B3%D0%BE-%D0%B3%D0%BE%D1%81%D1%83%D0%B4%D0%B0%D1%80%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B2%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%BD%D0%BE%D0%B3%D0%BE-%D1%81%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%B8%D1%82%D0%B0%D1%80%D0%BD%D0%BE%D0%B3%D0%BE-%D0%B2%D1%80%D0%B0%D1%87%D0%B0-%D0%BF%D0%BE-%D0%B3%D0%BE%D1%80%D0%BE%D0%B4%D1%83-%D1%81%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%BA%D1%82-%D0%BF%D0%B5%D1%82%D0%B5%D1%80%D0%B1%D1%83%D1%80%D0%B3%D1%83-%D0%BE%D1%82-12-10-2021-%E2%84%96-3-%C2%BB;jsessionid=FB3309CE788EBDCCB588450F5B1BE92F?redirect=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://ashspublications.org/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=fanisihi.com

http://cse.google.com.ly/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://cse.google.com.bh/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

https://pt.tapatalk.com/redirect.php?app_id=4&fid=8678&url=http://www.fanisihi.com

http://cse.google.co.tz/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=9BB77FDA801248A5AD23FDBDD5922800&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com

http://advisor.wmtransfer.com/SiteDetails.aspx?url=www.fanisihi.com

http://blogs.rtve.es/libs/getfirma_footer_prod.php?blogurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com

http://images.google.com.br/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://images.google.be/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://aboutus.com/Special:SiteAnalysis?q=fanisihi.com&action=webPresence

https://brettterpstra.com/share/fymdproxy.php?url=http://www.fanisihi.com

http://images.google.com.eg/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://my.myob.com/community/login.aspx?ReturnUrl=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://traceroute.physics.carleton.ca/cgi-bin/traceroute.pl?function=ping&target=fanisihi.com

http://cse.google.as/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://d-click.fiemg.com.br/u/18081/131/75411/137_0/82cb7/?url=https://fanisihi.com/

https://cse.google.ws/url?sa=t&url=http://fanisihi.com/

http://anonim.co.ro/?fanisihi.com/

http://id.telstra.com.au/register/crowdsupport?gotoURL=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://ads.businessnews.com.tn/dmcads2017/www/delivery/ck.php?ct=1&oaparams=2__bannerid=1839__zoneid=117__cb=df4f4d726f__oadest=https://fanisihi.com/

http://aichi-fishing.boy.jp/?wptouch_switch=desktop&redirect=http%3a%2f%2ffanisihi.com

http://cse.google.co.th/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.ch/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://images.google.cl/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://clients1.google.com.kh/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://client.paltalk.com/client/webapp/client/External.wmt?url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com%2F

http://clients1.google.com.lb/url?q=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com/

http://cam4com.go2cloud.org/aff_c?offer_id=268&aff_id=2014&url=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://creativecommons.org/choose/results-one?q_1=2&q_1=1&field_commercial=n&field_derivatives=sa&field_jurisdiction=&field_format=Text&field_worktitle=Blog&field_attribute_to_name=Lam%20HUA&field_attribute_to_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com%2F

http://images.google.cz/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://cse.google.co.bw/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://r.turn.com/r/click?id=07SbPf7hZSNdJAgAAAYBAA&url=https://fanisihi.com/

http://images.google.co.uk/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://images.google.com.bd/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://clients1.google.ge/url?q=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com/

http://2chmatome.jpn.org/akb/c_c.php?c_id=267977&url=https://fanisihi.com/

http://affiliate.suruga-ya.jp/modules/af/af_jump.php?user_id=755&goods_url=https://fanisihi.com/

http://archive.feedblitz.com/f/f.fbz?goto=https://fanisihi.com/

http://clients1.google.com.pr/url?sa=i&url=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://cse.google.com.gt/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://abcclub.cside.com/nagata/link4/link4.cgi?mode=cnt&hp=http%3a%2f%2ffanisihi.com&no=1027

http://clients1.google.com.fj/url?q=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://www.justjared.com/flagcomment.php?el=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com

http://clients1.google.com.gi/url?q=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com/

http://biz.timesfreepress.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=fanisihi.com

http://search.babylon.com/imageres.php?iu=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://clicktrack.pubmatic.com/AdServer/AdDisplayTrackerServlet?clickData=JnB1YklkPTE1NjMxMyZzaXRlSWQ9MTk5MDE3JmFkSWQ9MTA5NjQ2NyZrYWRzaXplaWQ9OSZ0bGRJZD00OTc2OTA4OCZjYW1wYWlnbklkPTEyNjcxJmNyZWF0aXZlSWQ9MCZ1Y3JpZD0xOTAzODY0ODc3ODU2NDc1OTgwJmFkU2VydmVySWQ9MjQzJmltcGlkPTU0MjgyODhFLTYwRjktNDhDMC1BRDZELTJFRjM0M0E0RjI3NCZtb2JmbGFnPTImbW9kZWxpZD0yODY2Jm9zaWQ9MTIyJmNhcnJpZXJpZD0xMDQmcGFzc2JhY2s9MA==_url=https://fanisihi.com/

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.bg/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://211-75-39-211.hinet-ip.hinet.net/Adredir.asp?url=https://fanisihi.com/

http://clients1.google.bg/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://ads2.figures.com/Ads3/www/delivery/ck.php?ct=1&oaparams=2__bannerid=282__zoneid=248__cb=da025c17ff__oadest=https%3a%2f%2ffanisihi.com

http://clients1.google.gy/url?q=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://clients1.google.com.ar/url?q=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://com.co.de/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=fanisihi.com

http://clients1.google.com.jm/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://home.speedbit.com/r.aspx?u=https://fanisihi.com/

http://cse.google.com.lb/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://blog.bg/results.php?q=%22%2f%3e%3ca+href%3d%22http%3a%2f%2ffanisihi.com&

http://images.google.com.co/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://clicrbs.com.br/paidcontent/jsp/login.jspx?site=545&url=goo.gl%2Fmaps%2FoQqZFfefPedXSkNc6&previousurl=http%3a%2f%2ffanisihi.com

http://clients1.google.kg/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://staging.talentegg.ca/redirect/company/224?destination=https://fanisihi.com/

http://images.google.co.za/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://clients1.google.com.co/url?q=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://cse.google.bf/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://cse.google.com.bz/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://cse.google.com.cu/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://www.talgov.com/Main/exit.aspx?url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com

http://cse.google.ci/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://blog.ss-blog.jp/_pages/mobile/step/index?u=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com

https://cse.google.tk/url?q=http://fanisihi.com/

http://www.siteprice.org/similar-websites/eden-project.org

http://clients1.google.ca/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://cse.google.cm/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://cse.google.ae/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://clients1.google.nr/url?q=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://imaginingourselves.globalfundforwomen.org/pb/External.aspx?url=https://fanisihi.com/

http://clients1.google.tk/url?q=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com/

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.co.il/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://theamericanmuslim.org/tam.php?URL=www.fanisihi.com

http://images.google.com.tr/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://thaiwebsearch.hypermart.net/cgi/clicko.pl?75&fanisihi.com

http://colil.dbcls.jp/fct/rdfdesc/usage.vsp?g=https://fanisihi.com/

https://content.sixflags.com/news/director.aspx?gid=0&iid=72&cid=3714&link=http://www.fanisihi.com/2021/05/29/rwfeds/

http://adr.tpprf.ru/bitrix/redirect.php?goto=https://fanisihi.com/

http://jump.2ch.net/?fanisihi.com

http://clients1.google.com.do/url?q=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://c.yam.com/msnews/IRT/r.c?https://fanisihi.com/

http://clients1.google.com.sa/url?sa=t&url=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

https://images.google.tk/url?q=http://fanisihi.com/

http://cse.google.com.gi/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://ad.sxp.smartclip.net/optout?url=https://fanisihi.com/&ang_testid=1

http://guru.sanook.com/?URL=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com%2F

http://clients1.google.com.my/url?sa=i&url=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://53938.measurementapi.com/serve?action=click&publisher_id=53938&site_id=69748&sub_campaign=g5e_com&url=https://fanisihi.com/

http://t.me/iv?url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com

http://clients1.google.co.ve/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://ayads.co/click.php?c=735-844&url=https://fanisihi.com/

http://campaigns.williamhill.com/C.ashx?btag=a_181578b_893c_&affid=1688431&siteid=181578&adid=893&c=&asclurl=https://fanisihi.com/&AutoR=1

http://www.aomeitech.com/forum/home/leaving?Target=https%3A//fanisihi.com

http://brandcycle.go2cloud.org/aff_c?offer_id=261&aff_id=1371&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://maps.google.de/url?sa=t&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com

http://webfeeds.brookings.edu/~/t/0/0/~www.fanisihi.com

http://images.google.co.za/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://clients1.google.com.ly/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://www.biblio.com.br/conteudo/Moldura11.asp?link=//www.fanisihi.com/2021/05/29/rwfeds/

http://store.veganessentials.com/affiliates/default.aspx?Affiliate=40&Target=https://www.fanisihi.com

http://images.google.be/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

https://cse.google.nu/url?q=http://fanisihi.com/

http://images.google.com.sa/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://cse.google.co.uz/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

https://www.trainorders.com/discussion/warning.php?forum_id=1&url=http://fanisihi.com/34zxVq8

http://audio.home.pl/redirect.php?action=url&goto=fanisihi.com&osCsid=iehkyctnmm

http://images.google.co.uk/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://ac8.i2i.jp/bin/getslink.php?00713417&&&https://fanisihi.com/

http://analytics.supplyframe.com/trackingservlet/track/?action=name&value3=1561&zone=FCfull_SRP_na_us&url=https://fanisihi.com/

http://adserver.gadu-gadu.pl/click.asp?adid=2236;url=https://fanisihi.com/

http://www.responsinator.com/?url=fanisihi.com

http://cse.google.cf/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://clients1.google.ga/url?q=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com/

http://m.ok.ru/dk?st.cmd=outLinkWarning&st.rfn=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com

http://cse.google.co.ck/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

https://www.wilsonlearning.com/?URL=fanisihi.com/

http://www.etis.ford.com/externalURL.do?url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com%2F

https://board-en.drakensang.com/proxy.php?link=http://fanisihi.com/

http://builder.hufs.ac.kr/goLink.jsp?url=fanisihi.com/

http://ahlacarte.vraiforum.com/redirect1/https://fanisihi.com/

https://images.google.cv/url?q=http://fanisihi.com/

http://clicktrack.pubmatic.com/AdServer/AdDisplayTrackerServlet?clickData=JnB1YklkPTE1NjMxMyZzaXRlSWQ9MTk5MDE3JmFkSWQ9MTA5NjQ2NyZrYWRzaXplaWQ9OSZ0bGRJZD00OTc2OTA4OCZjYW1wYWlnbklkPTEyNjcxJmNyZWF0aXZlSWQ9MCZ1Y3JpZD0xOTAzODY0ODc3ODU2NDc1OTgwJmFkU2VydmVySWQ9MjQzJmltcGlkPTU0MjgyODhFLTYwRjktNDhDMC1BRDZELTJFRjM0M0E0RjI3NCZtb2JmbGFnPTImbW9kZWxpZD0yODY2Jm9zaWQ9MTIyJmNhcnJpZXJpZD0xMDQmcGFzc2JhY2s9MA==_url=https://www.fanisihi.com/2021/05/29/rwfeds/

http://clients1.google.de/url?sa=t&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com

https://cse.google.cv/url?q=http://fanisihi.com/

http://cse.google.bi/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://app.guanajuato.gob.mx/revive/www/delivery/ck.php?oaparams=2__bannerid=2447__zoneid=88__cb=cb2b9a1cb1__oadest=http%3a%2f%2ffanisihi.com

http://subscriber.zdnet.de/profile/login.php?continue=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F&continue_label=ZDNet.de

http://aacollabarchive.humin.lsa.umich.edu/omeka/setlocale?locale=es&redirect=http%3a%2f%2ffanisihi.com

http://apptube.podnova.com/go/?go=https://fanisihi.com/

http://images.google.com.ua/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://www.kaskus.co.id/redirect?url=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://community.cypress.com/external-link.jspa?url=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

https://images.google.bs/url?q=http://fanisihi.com/

http://community.acer.com/en/home/leaving/www.fanisihi.com

http://daemon.indapass.hu/http/session_request?redirect_to=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com%2F&partner_id=bloghu

http://images.google.com.hk/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://clients1.google.je/url?q=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com/

http://www.novalogic.com/remote.asp?NLink=https://www.fanisihi.com/2021/05/29/rwfeds/

http://cm-sg.wargaming.net/frame/?service=frm&project=wot&realm=sg&language=en&login_url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com&logout_url=http%3A%2F%2Fforum.worldoftanks.asia%2Findex.php%3Fapp%3Dcore%26module%3Dglobal%26section%3Dlogin%26do%3Dlogoutoid&incomplete_profile_url=http%3A%2F%2Fforum.worldoftanks.asia%2Findex.php%3Fapp%3Dmembers%26module%3Dprofile%26do%3Ddocompleteaccount&token_url=http%3A%2F%2Fforum.worldoftanks.asia%2Fmenutoken&frontend_url=http%3A%2F%2Fcdn-cm.gcdn.co&backend_url=http%3A%2F%2Fcm-sg.wargaming.net&open_links_in_new_tab=¬ifications_enabled=1&chat_enabled=&incomplete_profile_notification_enabled=&intro_tooltips_enabled=1®istration_url=http%3A%2F%2Fforum.worldoftanks.asia%2Findex.php%3Fapp%3Dcore%26module%3Dglobal%26section%3Dregister

http://images.google.cz/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://cse.google.co.ug/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://sys.labaq.com/cli/go.php?s=lbac&p=1410jt&t=02&url=https://fanisihi.com/

http://clients1.google.cg/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://legacy.aom.org/verifymember.asp?nextpage=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com

http://clients1.google.iq/url?q=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com/

http://clients1.google.cv/url?q=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://cm-ru.wargaming.net/frame/?service=frm&project=wot&realm=ru&language=ru&login_url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com&logout_url=http%3A%2F%2Ffor

http://cse.google.co.uk/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

https://www.mydoterra.com/Application/index.cfm?EnrollerID=458046&Theme=DefaultTheme&Returnurl=fanisihi.com/&LNG=en_dot&iact=1

https://redirect.vebeet.com/index.php?url=//fanisihi.com/cities/tampa-fl/

http://cse.google.co.zw/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.at/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://www.adminer.org/redirect/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com&lang=en

https://webneel.com/i/3d-printer/5-free-3d-printer-model-website-yeggi/ei/12259?s=fanisihi.com/2021/05/29/rwfeds/

http://apf.francophonie.org/doc.html?url=https://fanisihi.com/

http://cse.google.by/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://www.jarrow.com/jump/http:_@__@_fanisihi.com

http://yahoo-mbga.jp/r?url=//fanisihi.com

http://www.pcpitstop.com/offsite.asp?https://www.fanisihi.com/

http://getpocket.com/redirect?url=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://cse.google.com.jm/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://cse.google.com.ec/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://www.drinksmixer.com/redirect.php?url=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://5cfxm.hxrs6.servertrust.com/v/affiliate/setCookie.asp?catId=1180&return=https://www.fanisihi.com

https://ditu.google.com/url?q=http://fanisihi.com/management.html

http://cse.google.co.ao/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://businesseast.ucoz.com/go?https://fanisihi.com/

https://www.streetwisereports.com/cs/blank/main?x-p=click/fwd&rec=ads/443&url=http://www.fanisihi.com/2021/05/29/rwfeds/

http://images.google.com.ec/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://www.sponsorship.com/Marketplace/redir.axd?ciid=514&cachename=advertising&PageGroupId=14&url=https://www.fanisihi.com

http://clients1.google.com.eg/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://cat.sls.cuhk.edu.hk/CRF/visualization?Species=https://fanisihi.com/

https://clients1.google.com/url?q=http://fanisihi.com/management.html

http://creativecommons.org/choose/results-one?q_1=2&q_1=1&field_commercial=n&field_derivatives=sa&field_jurisdiction=&field_format=Text&field_worktitle=Blog&field_attribute_to_name=Lam%20HUA&field_attribute_to_url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com%2F

http://tools.folha.com.br/print?url=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F&site=blogfolha

http://clients1.google.co.kr/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://apiprop.sulekha.com/common/apploginredirect.aspx?enclgn=ilsxyvoDCT5XZjQCeHI5qlKoZ3Ljv/1wHK3AR7dYYz8%3D&nexturl=https://fanisihi.com/

http://cse.google.de/url?sa=t&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com

http://images.google.dk/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://avp.innity.com/click/?campaignid=10933&adid=115198&zoneid=39296&pubid=3194&ex=1412139790&pcu=&auth=3tx88b-1412053876272&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://ads.haberler.com/redir.asp?tur=habericilink&url=https://fanisihi.com/

http://ip.tool.chinaz.com/?ip=fanisihi.com

http://ax.bk55.ru/cur/www/delivery/ck.php?ct=1&oaparams=2__bannerid=4248__zoneid=141__OXLCA=1__cb=1be00d870a__oadest=https://fanisihi.com/

http://support.dalton.missouri.edu/?URL=fanisihi.com

http://banri.moo.jp/-18/?wptouch_switch=desktop&redirect=https%3a%2f%2ffanisihi.com

http://avatar-cat-ru.1gb.ru/index.php?name=plugins&p=out&url=fanisihi.com

http://sogo.i2i.jp/link_go.php?url=https://fanisihi.com/

http://clients1.google.co.ug/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://cse.google.cd/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://www.t.me/iv?url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com

http://www.ibm.com/links/?cc=us&lc=en&prompt=1&url=//fanisihi.com

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.co.ao/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://clients1.google.co.ke/url?sa=t&url=https://fanisihi.com/

http://cse.google.al/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://dotekomanie.cz/heureka/?url=https%3a%2f%2ffanisihi.com%2F

http://images.google.co.id/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://images.google.de/url?sa=t&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com

https://maps.google.tk/url?q=http://fanisihi.com/

http://www.astro.wisc.edu/?URL=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com

http://images.google.com.br/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://cse.google.co.ke/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://cse.google.co.il/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://api.fooducate.com/fdct/message/t/?t=592390BA-2F20-0472-4BA5-A59870BBA6A2:61213861:5AFC37A3-CAD4-CC42-4921-9BE2094B0A14&a=c&d=https://fanisihi.com/

http://armenaikkandomainrating5.blogspot.com0.vze.com/frame-forward.cgi?https://fanisihi.com/

http://cse.google.co.in/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://subscriber.silicon.co.uk/profile/login.php?continue=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F&continue_label=TechWeekEurope+UK

http://cse.google.com.bn/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://images.google.com.do/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.com.lb/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://cr.naver.com/redirect-notification?u=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com

http://images.google.com.au/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://brangista.j-server.com/BRASADAIJ/ns/tl_ex.cgi?Surl=https://fanisihi.com/

http://beskuda.ucoz.ru/go?https://fanisihi.com/

http://uriu-ss.jpn.org/xoops/modules/wordpress/wp-ktai.php?view=redir&url=http%3a%2f%2ffanisihi.com

http://cse.google.com.ai/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://cse.google.cat/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://www.luminous-lint.com/app/iframe/photographer/Frantisek__Drtikol/fanisihi.com

http://onlinemanuals.txdot.gov/help/urlstatusgo.html?url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com

http://click.karenmillen.com/knmn40/c2.php?KNMN/94073/5285/H/N/V/https://fanisihi.com/

http://images.google.com.pe/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://images.google.ee/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://ar.thefreedictionary.com/_/cite.aspx?url=http%3a%2f%2ffanisihi.com&word=%D8%AD%D9%8E%D9%84%D9%90%D9%85%D9%8E&sources=kdict

http://bigtakeover.com/revive/www/delivery/ck.php?ct=1&oaparams=2__bannerid=68__zoneid=4__cb=c0575383b9__oadest=https://fanisihi.com/

http://circuitomt.com.br/publicidade/www/delivery/ck.php?ct=1&oaparams=2__bannerid=34__zoneid=2__cb=6cc35441a4__oadest=http%3a%2f%2ffanisihi.com

http://akid.s17.xrea.com/p2ime.php?url=https://fanisihi.com/

http://clients1.google.com.tr/url?sa=t&url=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://links.giveawayoftheday.com/fanisihi.com

http://www2.ogs.state.ny.us/help/urlstatusgo.html?url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com

http://images.google.co.il/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://bompasandparr.com/?URL=https://fanisihi.com/

http://cse.google.com.ag/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://new.creativecommons.org/choose/results-one?q_1=2&q_1=1&field_commercial=n&field_derivatives=sa&field_jurisdiction=&field_format=Text&field_worktitle=Blog&field_attribute_to_name=Lam%20HUA&field_attribute_to_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com%2F

http://optimize.viglink.com/page/pmv?url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com

http://cse.google.com.co/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://blackfive.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=fanisihi.com

http://api.mixpanel.com/track/?data=eyJldmVudCI6ICJmdWxsdGV4dGNsaWNrIiwgInByb3BlcnRpZXMiOiB7InRva2VuIjogImE0YTQ2MGEzOTA0ZWVlOGZmNWUwMjRlYTRiZGU3YWMyIn19&ip=1&redirect=https://fanisihi.com/

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.bs/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://video.fc2.com/exlink.php?uri=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://cse.google.co.jp/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://images.google.es/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.co.za/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://ads.bhol.co.il/clicks_counter.asp?macrocid=5635&campid=177546&DB_link=0&userid=0&ISEXT=0&url=https://fanisihi.com/

http://cse.google.be/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://at070582.xsrv.jp/?wptouch_switch=desktop&redirect=http%3a%2f%2ffanisihi.com

http://u.to/?url=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F&a=add

http://ipv4.google.com/url?q=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com%2F

http://cse.google.co.ve/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://catzlyst.phrma.org/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=fanisihi.com

http://clients1.google.co.jp/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://clients1.google.com.hk/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://clients1.google.cd/url?sa=t&url=https://fanisihi.com/

http://bares.blog.idnes.cz/redir.aspx?url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com

http://www.ip-adress.com/website/fanisihi.com

http://clients1.google.st/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://cse.google.co.vi/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://cse.google.com.br/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://parkcities.bubblelife.com/click/c3592/?url=https://fanisihi.com/

http://clients1.google.by/url?sa=t&url=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://antigo.anvisa.gov.br/listagem-de-alertas/-/asset_publisher/R6VaZWsQDDzS/content/alerta-3191-tecnovigilancia-boston-scientific-do-brasil-ltda-fibra-optica-greenlight-possibilidade-de-queda-de-temperatura-da-tampa-de-metal-e-da-pont/33868?inheritRedirect=false&redirect=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://cse.google.ca/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://cse.google.com.au/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://ads.hitparade.ch/link.php?ad_id=28&url=https://fanisihi.com/

http://clients1.google.tm/url?q=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com/

http://images.google.com.pk/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://cc.cgps.tn.edu.tw/dyna/netlink/hits.php?id=46&url=https://fanisihi.com/

http://cse.google.co.ma/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://clients1.google.ne/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://cse.google.com.et/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://nou-rau.uem.br/nou-rau/zeus/auth.php?back=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com%2F&go=x&code=x&unit=x

http://cc.naver.jp/cc?a=dtl.topic&r=&i=&bw=1024&px=0&py=0&sx=-1&sy=-1&m=1&nsc=knews.viewpage&u=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com

http://images.google.com.mx/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://cse.google.com.fj/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://a1.adform.net/C/?CC=1&bn=1015999%3Bc=1%3Bkw=Forex%20Trading%3Bcpdir=https://fanisihi.com/

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.com.br/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://cse.google.com.hk/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://catalog.dir.bg/url.php?URL=https://fanisihi.com/

http://clients1.google.it/url?q=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com/

http://counter.iflyer.tv/?trackid=gjt:1:&link=https://fanisihi.com/

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.co.vi/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://admin.billoreilly.com/site/rd?satype=13&said=12&url=https://fanisihi.com/

http://clients1.google.mn/url?q=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://backlink.scandwap.xtgem.com/?id=IRENON&url=fanisihi.com

https://www.videoder.com/af/media?mode=2&url=http://www.fanisihi.com

http://ad.gunosy.com/pages/redirect?location=https://fanisihi.com/

http://pw.mail.ru/forums/fredirect.php?url=www.fanisihi.com

http://armoryonpark.org/?URL=https://fanisihi.com/

http://app.hamariweb.com/iphoneimg/large.php?s=https://fanisihi.com/

http://enseignants.flammarion.com/Banners_Click.cfm?ID=86&URL=www.fanisihi.com

http://decisoes.fazenda.gov.br/netacgi/nph-brs?d=DECW&f=S&l=20&n=-DTPE&p=10&r=3&s1=COANA&u=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com

http://clients1.google.am/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://www.transtats.bts.gov/exit.asp?url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com%2F

http://archive.aidsmap.com/Aggregator.ashx?url=https://fanisihi.com/

http://countrysideveterinaryhospital.vetstreet.com/https://fanisihi.com/

http://images.google.bg/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://pl.grepolis.com/start/redirect?url=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

https://www.google.ws/url?q=http://fanisihi.com/

http://banners.molbiol.ru/openx/www/delivery/ck.php?ct=1&oaparams=2__bannerid=552__zoneid=16__cb=70ec3bb20d__oadest=http%3a%2f%2ffanisihi.com

http://archive.is/fanisihi.com

http://blogs.rtve.es/libs/getfirma_footer_prod.php?blogurl=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://asoechat.wap.sh/redirect?url=fanisihi.com

http://images.google.com.co/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://cse.google.ch/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://classweb.fges.tyc.edu.tw:8080/dyna/webs/gotourl.php?url=https://fanisihi.com/

http://adms3.hket.com/openxprod2/www/delivery/ck.php?ct=1&oaparams=2__bannerid=527__zoneid=667__cb=72cbf61f88__oadest=https://fanisihi.com/

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.co.ls/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://cse.google.bg/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://ijbssnet.com/view.php?u=https://www.fanisihi.com/2021/05/29/rwfeds/

http://affiliates.thelotter.com/aw.aspx?A=1&Task=Click&ml=31526&TargetURL=https://fanisihi.com/

http://777masa777.lolipop.jp/search/rank.cgi?mode=link&id=83&url=http%3a%2f%2ffanisihi.com

http://images.google.com.my/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://b.gnavi.co.jp/ad/no_cookie/b_link?loc=1002067&bid=100004228&link_url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://www.drugoffice.gov.hk/gb/unigb/fanisihi.com

http://clients1.google.bj/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://bizsearch.jhnewsandguide.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=fanisihi.com

http://adms.hket.com/openxprod2/www/delivery/ck.php?ct=1&oaparams=2__bannerid=6685__zoneid=2040__cb=dfaf38fc52__oadest=http%3a%2f%2ffanisihi.com

http://es.chaturbate.com/external_link/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com

http://images.google.com.uy/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

https://cse.google.com/url?q=http://fanisihi.com/management.html

http://12.rospotrebnadzor.ru/action_plans/inspection/-/asset_publisher/iqO1/document/id/460270?_101_INSTANCE_iqO1_redirect=https://fanisihi.com/

http://bigoo.ws/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=fanisihi.com

https://www.raincoast.com/?URL=fanisihi.com

http://clients1.google.ci/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://ref.webhostinghub.com/scripts/click.php?ref_id=nichol54&desturl=https://fanisihi.com/

http://web.stanford.edu/cgi-bin/redirect?dest=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com

https://cse.google.tk/url?sa=t&url=http://fanisihi.com/

http://community.esri.com/external-link.jspa?url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com

http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com

http://cse.google.com.kw/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://ads.specificmedia.com/click/v=5;m=2;l=23470;c=146418;b=874880;p=ui=ACXqoRFLEtwSFA;tr=DZeqTyQW0qH;tm=0-0;ts=20110427233838;dct=https://fanisihi.com/

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.co.id/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://digital.fijitimes.com/api/gateway.aspx?f=https://www.fanisihi.com

http://rd.rakuten.co.jp/a/?R2=https%3A//fanisihi.com/

http://www3.valueline.com/vlac/logon.aspx?lp=https://www.fanisihi.com

http://bpx.bemobi.com/opx/5.0/OPXIdentifyUser?Locale=uk&SiteID=402698301147&AccountID=202698299566&ecid=KR5t1vLv9P&AccessToken=&RedirectURL=https://fanisihi.com/

http://www.economia.unical.it/prova.php?a%5B%5D=%3Ca+href%3Dhttps%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://br.nate.com/diagnose.php?from=w&r_url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.bj/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://images.google.com.tw/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

https://www.xcelenergy.com/stateselector?stateselected=true&goto=http://fanisihi.com

http://www.film1.nl/zoek/?q=%22%2F%3E%3Ca+href%3D%22https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F&sa=&cx=009153552854938002534%3Aaf0ze8etbks&ie=ISO-8859-1&cof=FORID%3

https://cse.google.com/url?sa=t&url=http://fanisihi.com/

http://clients1.google.co.il/url?sa=i&url=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.com.np/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://images.google.com.vn/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://ads1.opensubtitles.org/1/www/delivery/afr.php?zoneid=3&cb=984766&query=One+Froggy+Evening&landing_url=https://fanisihi.com/

http://adrian.edu/?URL=https://fanisihi.com/

http://bidr.trellian.com/r.php?u=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

https://www.htcdev.com/?URL=fanisihi.com

http://aid97400.lautre.net/spip.php?action=cookie&url=https://fanisihi.com/

https://doterra.myvoffice.com/Application/index.cfm?&EnrollerID=604008&Theme=Default&ReturnUrl=http://fanisihi.com

http://images.google.com.mx/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://cse.google.cg/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://images.google.co.th/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://clients1.google.gl/url?q=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://fftoolbox.fulltimefantasy.com/search.cfm?q=%22%2F%3E%3Ca+href%3D%22https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://images.google.com.bd/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://clients1.google.co.za/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://cse.google.co.id/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://fanisihi.com.ipaddress.com/

http://cgi.davec.plus.com/cgi-bin/logs/loglink.cgi?https://fanisihi.com/

http://forms.bl.uk/newsletters/index.aspx?back=https%3A//fanisihi.com/

https://tour.catalinacruz.com/pornstar-gallery/puma-swede-face-sitting-on-cassie-young-lesbian-fun/?link=http://www.fanisihi.com/holostyak-stb-2021

http://www.youtube.com/redirect?q=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com%2F

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.com.vc/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://bulkmail.doh.state.fl.us/lt.php?c=102&m=144&nl=18&lid=922&l=https://fanisihi.com/

http://sc.sie.gov.hk/TuniS/fanisihi.com

http://images.google.cl/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://images.google.ae/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.tg/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://images.google.com.ng/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://images.google.fi/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://cse.google.cl/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://images.google.com.vn/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://cse.google.ad/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

https://partnerpage.google.com/url?sa=i&url=http://fanisihi.com/

http://clients1.google.tg/url?q=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://images.google.co.il/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://clients1.google.nu/url?q=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com/

https://services.celemony.com/cgi-bin/WebObjects/LicenseApp.woa/wa/MCFDirectAction/link?linkId=1001414&stid=3463129&url=www.fanisihi.com/2021/05/29/rwfeds/

http://cse.google.co.zm/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

https://200-155-82-24.bradesco.com.br/conteudo/pessoa-fisica/popExt.aspx?url=http://fanisihi.com/2021/05/29/rwfeds/

http://a.twiago.com/adclick.php?tz=1473443342212991&pid=198&kid=2365&wmid=14189&wsid=65&uid=28&sid=3&sid2=2&swid=8950&ord=1473443342&target=https://fanisihi.com/

http://clients1.google.ee/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://clients1.google.co.nz/url?sa=t&url=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.ac/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://m.odnoklassniki.ru/dk?st.cmd=outLinkWarning&st.rfn=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com

https://www.qscience.com/locale/redirect?redirectItem=http://www.fanisihi.com

http://cse.google.co.za/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://111.1gb.ru/go.php?https://fanisihi.com/

http://images.google.co.in/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.com.my/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://aqua21.jpn.org/lateequ/navi/navi.cgi?&mode=jump&id=6936&url=fanisihi.com

http://webmail.mawebcenters.com/parse.pl?redirect=https://www.fanisihi.com

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.cf/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://cse.google.com.gh/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

https://www.google.bs/url?q=http://fanisihi.com/

http://as.inbox.com/AC.aspx?id_adr=262&link=https://fanisihi.com/

http://cse.google.com.do/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://www.cssdrive.com/?URL=fanisihi.com/holostyak-stb-2021

https://advtest.exibart.com/adv/adv.php?id_banner=7201&link=http://www.fanisihi.com/2021/05/29/rwfeds/

http://images.google.com.eg/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://ad.foxitsoftware.com/adlog.php?a=redirect&img=testad&url=fanisihi.com

http://chtbl.com/track/118167/fanisihi.com/

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.com.af/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

https://maps.google.nu/url?q=http://fanisihi.com/

http://images.google.com.tw/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

https://maps.google.ws/url?q=http://fanisihi.com/

http://action.metaffiliation.com/redir.php?u=https://fanisihi.com/

http://bons-plans-astuces.digidip.net/visit?url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://crash-ut3.clan.su/go?https://fanisihi.com/

http://cse.google.co.cr/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://archives.richmond.ca/archives/descriptions/results.aspx?AC=SEE_ALSO&QF0=NameAccess&QI0==%22Currie%20McWilliams%20Camp%22&XC=http%3a%2f%2ffanisihi.com&BU=https%3a%2f%2fcutepix.info%2fsex%2friley-reyes.php&TN=Descriptions&SN=AUTO19204&SE=1790&RN=2&MR=20&TR=0&TX=1000&ES=0&CS=0&XP=&RF=WebBrief&EF=&DF=WebFull&RL=0&EL=0&DL=0&NP=255&ID=&MF=GENERICENGWPMSG.INI&MQ=&TI=0&DT=&ST=0&IR=173176&NR=1&NB=0&SV=0&SS=0&BG=&FG=&QS=&OEX=ISO-8859-1&OEH=utf-8

http://plus.google.com/url?q=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com%2F

https://www.horseillustrated.com/redirect.php?location=http://www.fanisihi.com

http://whois.domaintools.com/fanisihi.com

http://cse.google.com.kh/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://www.timeandtiming.com/?&URL=fanisihi.com

http://arhvak.minobrnauki.gov.ru/c/document_library/find_file_entry?p_l_id=17390&noSuchEntryRedirect=https://fanisihi.com/

https://posts.google.com/url?q=http://fanisihi.com/management.html

http://wtk.db.com/777554543598768/optout?redirect=https://www.fanisihi.com

http://images.google.ca/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://app.feedblitz.com/f/f.fbz?track=fanisihi.com

http://nutritiondata.self.com/facts/recipe/1304991/2?mbid=HDFD&trackback=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.www.fanisihi.com

http://images.google.co.nz/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.is/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://ts.videosz.com/out.php?cid=101&aid=102&nis=0&srid=392&url=https://fanisihi.com/

https://www.google.tk/url?q=http://fanisihi.com/

http://clients1.google.co.ao/url?q=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com/

http://amaterasu.dojin.com/home/ranking.cgi?ti=%94%92%82%C6%8D%95%82%CC%94%FC%8Aw%81B&HP=http%3a%2f%2ffanisihi.com&ja=3&id=19879&action=regist

http://www.astronet.ru/db/msusearch/index.html?q=%3Ca+href%3Dhttps%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://images.google.com.sg/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

https://bugcrowd.com/external_redirect?site=http://www.fanisihi.com

http://biwa28.lolipop.jp/ys100/rank.cgi?mode=link&id=1290&url=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://fcaw.library.umass.edu/goto/https:/www.fanisihi.com

http://radio.cancaonova.com/iframe-loader/?t=DatingSingle:NoLongeraMystery-R�dio&ra=&url=https://www.fanisihi.com/2021/05/29/rwfeds/

https://cse.google.nr/url?sa=t&url=http://fanisihi.com/

http://clients1.google.gg/url?q=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://cse.google.bj/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://camiane.dmcart.gethompy.com/shop/bannerhit.php?bn_id=91&url=http%3a%2f%2ffanisihi.com

https://www.relativitymedia.com/logout?redirect=//www.fanisihi.com/

http://anoushkabold.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=fanisihi.com

http://cse.google.com.cy/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://cse.google.am/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

https://www.meetme.com/apps/redirect/?url=http://fanisihi.com

http://cse.google.at/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://legacy.aom.org/verifymember.asp?nextpage=https%3A//fanisihi.com/

https://images.google.nu/url?q=http://fanisihi.com/

https://images.google.ws/url?q=http://fanisihi.com/

http://clients1.google.com.et/url?q=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://cse.google.bs/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

https://mitsui-shopping-park.com/lalaport/iwata/redirect.html?url=http://fanisihi.com/

https://www.barrypopik.com/index.php?URL=http://www.fanisihi.com

http://clients1.google.com.om/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://bioinfo3d.cs.tau.ac.il/wk/api.php?action=https://fanisihi.com/

http://contacts.google.com/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com

http://sc.hkex.com.hk/gb/fanisihi.com

http://cse.google.com.bo/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://cse.google.co.nz/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

https://www.extremnews.com/nachrichten/standard/dereferrer.cfm?rurl=http://www.fanisihi.com/2021/05/29/rwfeds/

http://cse.google.co.ls/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://portal.novo-sibirsk.ru/dynamics.aspx?PortalId=2&WebId=8464c989-7fd8-4a32-8021-7df585dca817&PageUrl=%2FSitePages%2Ffeedback.aspx&Color=B00000&Source=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://clients1.google.com.gh/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.com.pe/url?q=https%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://clients1.google.jo/url?q=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://clients1.google.pn/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

https://cse.google.nu/url?sa=t&url=http://fanisihi.com/

http://cse.google.ba/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://www.venez.fr/error.fr.html?id=1&uri=https%3A//fanisihi.com/

http://domain.opendns.com/fanisihi.com

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.com.ua/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.be/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

https://www.allergicliving.com/adspace/?mod=serve&act=clickthru&id=695&to=http://www.fanisihi.com/2021/05/29/rwfeds/

http://cse.google.com.bd/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://aborg.lib.ntu.edu.tw/ntuepaper/toModule.do?prefix=/publish&page=/newslist.jsp&uri=https://fanisihi.com/

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.pl/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://images.google.fi/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://blawat2015.no-ip.com/~mieki256/diary/refsweep.cgi?url=https://fanisihi.com/

https://www.google.nu/url?q=http://fanisihi.com/

http://images.google.co.jp/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

https://www.dltk-teach.com/p.asp?p=http://www.fanisihi.com/2021/05/29/rwfeds/

http://images.google.co.id/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://images.google.com.my/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://members.ascrs.org/sso/logout.aspx?returnurl=https://fanisihi.com/

http://closings.cbs6albany.com/scripts/adredir.asp?url=https://fanisihi.com/

http://images.google.co.th/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://alumni.drivers.informer.com/go/go.php?go=https://fanisihi.com/

http://uriu-ss.jpn.org/xoops/modules/wordpress/wp-ktai.php?view=redir&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.com.kw/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://forum.solidworks.com/external-link.jspa?url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fanisihi.com

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.bf/url?q=https://fanisihi.com/

http://acf.poderjudicial.es/portal/site/cgpj/menuitem.65d2c4456b6ddb628e635fc1dc432ea0/?schema=http&title=Acuerdos+de+la+Comisi%C3%B3n+Permanente+del+CGPJ+de+17+de+julio+de+2018&vgnextoid=d94e58e4d849d210VgnVCM100000cb34e20aRCRD&vgnextlocale=gl&isSecure=false&vgnextfmt=default&protocolo=http&user=&url=http%3a%2f%2ffanisihi.com&perfil=3

http://0845.boo.jp/cgi/mt3/mt4i.cgi?id=24&mode=redirect&no=15&ref_eid=3387&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com

http://cse.google.co.kr/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffanisihi.com%2F

http://hostedmovieupdates.aebn.net/feed/?urlstub=fanisihi.com&

sex,porn,nude videos,new sex videos,sex video,watch porn,sex porn,nude sex,latest porn watch\

https://www.mid-day.com/brand-media/article/fit-today-wellness-keto-gummies-reviews-scam-exposed-what-you-need-to-know-23275442

buy viagra online

buy viagra online

Excellent post. I was checking continuously

this weblog and I’m impressed! Very helpful info specially the last part 🙂 I care for such information much.

I was seeking this particular information for a long

time. Thanks and best of luck.

My page :: free v bucks generator

http://www.youtube.com/redirect?event=channel_description&q=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.lrtt.lt%2F

http://cse.google.com.eg/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt%2F

http://cn.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?COLLCC=1718906003&ref=FexRss&aid=&url=https://lrtt.lt/

http://images.google.com.sa/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt

http://images.google.at/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt

http://images.google.com/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt

http://images.google.gr/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt%2F

http://images.google.com.ua/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt%2F

http://accounts.cancer.org/login?redirectURL=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.lrtt.lt&theme=RFL

https://images.google.tk/url?sa=t&url=http://lrtt.lt/

http://images.google.ee/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt%2F

http://clients1.google.ki/url?q=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt

http://clients1.google.td/url?q=https%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt

https://website.informer.com/lrtt.lt

http://clients1.google.at/url?q=https%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.com.ec/url?q=https://lrtt.lt/

http://b.filmz.ru/presentation/www/delivery/ck.php?ct=1&oaparams=2__bannerid=222__zoneid=2__cb=93494e485e__oadest=https://lrtt.lt/

http://ava-online.clan.su/go?https://lrtt.lt/

http://ads.dfiles.eu/click.php?c=1497&z=4&b=1730&r=https://lrtt.lt/

http://clinica-elit.vrn.ru/cgi-bin/inmakred.cgi?bn=43252&url=lrtt.lt

http://chat.chat.ru/redirectwarn?https://lrtt.lt/

http://cm-eu.wargaming.net/frame/?service=frm&project=moo&realm=eu&language=en&login_url=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt

http://maps.google.com/url?q=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.lrtt.lt%2F

http://audit.tomsk.ru/bitrix/click.php?goto=https://lrtt.lt/

http://clients1.google.co.mz/url?q=https%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt/

http://come-on.rdy.jp/wanted/cgi-bin/rank.cgi?id=11326&mode=link&url=https://lrtt.lt/

http://images.google.com.ng/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt%2F

http://yumi.rgr.jp/puku-board/kboard.cgi?mode=res_html&owner=proscar&url=lrtt.lt/&count=1&ie=1

http://images.google.com.au/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt%2F

https://asia.google.com/url?q=http://lrtt.lt/management.html

http://adapi.now.com/ad/api/act.ashx?a=2&sc=3490&s=30000219&l=1&t=0&c=0&u=https://lrtt.lt/

https://cse.google.ws/url?q=http://lrtt.lt/

http://avn.innity.com/click/avncl.php?bannerid=68907&zoneid=0&cb=2&pcu=&url=http%3a%2f%2flrtt.lt

https://ross.campusgroups.com/click?uid=51a11492-dc03-11e4-a071-0025902f7e74&r=http://lrtt.lt/

http://images.google.de/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt

http://tools.folha.com.br/print?url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.lrtt.lt%2F&site=blogfolha

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.com.fj/url?q=https://lrtt.lt/

http://new.creativecommons.org/choose/results-one?q_1=2&q_1=1&field_commercial=n&field_derivatives=sa&field_jurisdiction=&field_format=Text&field_worktitle=Blog&field_attribute_to_name=Lam%20HUA&field_attribute_to_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.lrtt.lt

http://redirect.subscribe.ru/bank.banks

http://www.so-net.ne.jp/search/web/?query=lrtt.lt&from=rss

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.cat/url?q=https://lrtt.lt/

http://affiliate.awardspace.info/go.php?url=https://lrtt.lt/

http://writer.dek-d.com/dek-d/link/link.php?out=https%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt%2F&title=lrtt.lt

http://analogx.com/cgi-bin/cgirdir.exe?https://lrtt.lt/

http://images.google.co.ve/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt%2F

http://ip.chinaz.com/?IP=lrtt.lt

http://images.google.com.pe/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt%2F

http://cmbe-console.worldoftanks.com/frame/?language=en&login_url=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt&project=wotx&realm=wgcb&service=frm

http://images.google.dk/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt

http://ceramique-et-couleurs.leforum.eu/redirect1/https://lrtt.lt/

https://ipv4.google.com/url?q=http://lrtt.lt/management.html

http://cse.google.com.af/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt%2F

http://images.google.com.do/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt%2F

http://newsdiffs.org/article-history/lrtt.lt/

http://cse.google.az/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt%2F

http://images.google.ch/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt

http://aganippe.online.fr/lien.php3?url=http%3a%2f%2flrtt.lt

http://images.google.fr/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt

http://images.google.co.ve/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.com.do/url?q=https://lrtt.lt/

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.co.mz/url?q=https://lrtt.lt/

https://www.easyviajar.com/me/link.jsp?site=359&client=1&id=110&url=http://www.lrtt.lt/2021/05/29/rwfeds/

http://68-w.tlnk.io/serve?action=click&site_id=137717&url_web=https://lrtt.lt/

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.sk/url?q=https://lrtt.lt/

http://jump.2ch.net/?www.lrtt.lt

http://images.google.co.nz/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt

http://images.google.com.ec/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.com.mx/url?q=https://lrtt.lt/

http://sitereport.netcraft.com/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.lrtt.lt%2F

http://www.ursoftware.com/downloadredirect.php?url=https%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt%2F

http://cse.google.co.mz/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt%2F

http://legal.un.org/docs/doc_top.asp?path=../ilc/documentation/english/a_cn4_13.pd&Lang=Ef&referer=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.lrtt.lt%2F

http://doodle.com/r?url=https%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt%2F

http://cse.google.ac/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt%2F

http://78.rospotrebnadzor.ru/news9/-/asset_publisher/9Opz/content/%D0%BF%D0%BE%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%BE%D0%B2%D0%BB%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%B5-%D0%B3%D0%BB%D0%B0%D0%B2%D0%BD%D0%BE%D0%B3%D0%BE-%D0%B3%D0%BE%D1%81%D1%83%D0%B4%D0%B0%D1%80%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B2%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%BD%D0%BE%D0%B3%D0%BE-%D1%81%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%B8%D1%82%D0%B0%D1%80%D0%BD%D0%BE%D0%B3%D0%BE-%D0%B2%D1%80%D0%B0%D1%87%D0%B0-%D0%BF%D0%BE-%D0%B3%D0%BE%D1%80%D0%BE%D0%B4%D1%83-%D1%81%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%BA%D1%82-%D0%BF%D0%B5%D1%82%D0%B5%D1%80%D0%B1%D1%83%D1%80%D0%B3%D1%83-%E2%84%96-4-%D0%BE%D1%82-09-11-2021-%C2%AB%D0%BE-%D0%B2%D0%BD%D0%B5%D1%81%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%B8-%D0%B8%D0%B7%D0%BC%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%B8-%D0%B2-%D0%BF%D0%BE%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%BE%D0%B2%D0%BB%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%B5-%D0%B3%D0%BB%D0%B0%D0%B2%D0%BD%D0%BE%D0%B3%D0%BE-%D0%B3%D0%BE%D1%81%D1%83%D0%B4%D0%B0%D1%80%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B2%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%BD%D0%BE%D0%B3%D0%BE-%D1%81%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%B8%D1%82%D0%B0%D1%80%D0%BD%D0%BE%D0%B3%D0%BE-%D0%B2%D1%80%D0%B0%D1%87%D0%B0-%D0%BF%D0%BE-%D0%B3%D0%BE%D1%80%D0%BE%D0%B4%D1%83-%D1%81%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%BA%D1%82-%D0%BF%D0%B5%D1%82%D0%B5%D1%80%D0%B1%D1%83%D1%80%D0%B3%D1%83-%D0%BE%D1%82-12-10-2021-%E2%84%96-3-%C2%BB;jsessionid=FB3309CE788EBDCCB588450F5B1BE92F?redirect=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt

http://ashspublications.org/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=lrtt.lt

http://cse.google.com.ly/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt%2F

http://cse.google.com.bh/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt%2F

https://pt.tapatalk.com/redirect.php?app_id=4&fid=8678&url=http://www.lrtt.lt

http://cse.google.co.tz/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt%2F

http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=9BB77FDA801248A5AD23FDBDD5922800&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.lrtt.lt

http://advisor.wmtransfer.com/SiteDetails.aspx?url=www.lrtt.lt

http://blogs.rtve.es/libs/getfirma_footer_prod.php?blogurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.lrtt.lt

http://images.google.com.br/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt

http://images.google.be/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt%2F

http://aboutus.com/Special:SiteAnalysis?q=lrtt.lt&action=webPresence

https://brettterpstra.com/share/fymdproxy.php?url=http://www.lrtt.lt

http://images.google.com.eg/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt

http://my.myob.com/community/login.aspx?ReturnUrl=https%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt%2F

http://traceroute.physics.carleton.ca/cgi-bin/traceroute.pl?function=ping&target=lrtt.lt

http://cse.google.as/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt%2F

http://d-click.fiemg.com.br/u/18081/131/75411/137_0/82cb7/?url=https://lrtt.lt/

https://cse.google.ws/url?sa=t&url=http://lrtt.lt/

http://anonim.co.ro/?lrtt.lt/

http://id.telstra.com.au/register/crowdsupport?gotoURL=https%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt%2F

http://ads.businessnews.com.tn/dmcads2017/www/delivery/ck.php?ct=1&oaparams=2__bannerid=1839__zoneid=117__cb=df4f4d726f__oadest=https://lrtt.lt/

http://aichi-fishing.boy.jp/?wptouch_switch=desktop&redirect=http%3a%2f%2flrtt.lt

http://cse.google.co.th/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt%2F

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.ch/url?q=https://lrtt.lt/

http://images.google.cl/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt

http://clients1.google.com.kh/url?q=https://lrtt.lt/

http://client.paltalk.com/client/webapp/client/External.wmt?url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.lrtt.lt%2F

http://clients1.google.com.lb/url?q=https%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt/

http://cam4com.go2cloud.org/aff_c?offer_id=268&aff_id=2014&url=https%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt

http://creativecommons.org/choose/results-one?q_1=2&q_1=1&field_commercial=n&field_derivatives=sa&field_jurisdiction=&field_format=Text&field_worktitle=Blog&field_attribute_to_name=Lam%20HUA&field_attribute_to_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.lrtt.lt%2F

http://images.google.cz/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt

http://cse.google.co.bw/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt%2F

http://r.turn.com/r/click?id=07SbPf7hZSNdJAgAAAYBAA&url=https://lrtt.lt/

http://images.google.co.uk/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt%2F

http://images.google.com.bd/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt

http://clients1.google.ge/url?q=https%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt/

http://2chmatome.jpn.org/akb/c_c.php?c_id=267977&url=https://lrtt.lt/

http://affiliate.suruga-ya.jp/modules/af/af_jump.php?user_id=755&goods_url=https://lrtt.lt/

http://archive.feedblitz.com/f/f.fbz?goto=https://lrtt.lt/

http://clients1.google.com.pr/url?sa=i&url=https%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt

http://cse.google.com.gt/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt%2F

http://abcclub.cside.com/nagata/link4/link4.cgi?mode=cnt&hp=http%3a%2f%2flrtt.lt&no=1027

http://clients1.google.com.fj/url?q=https%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt

http://www.justjared.com/flagcomment.php?el=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.lrtt.lt

http://clients1.google.com.gi/url?q=https%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt/

http://biz.timesfreepress.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=lrtt.lt

http://search.babylon.com/imageres.php?iu=https%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt%2F

http://clicktrack.pubmatic.com/AdServer/AdDisplayTrackerServlet?clickData=JnB1YklkPTE1NjMxMyZzaXRlSWQ9MTk5MDE3JmFkSWQ9MTA5NjQ2NyZrYWRzaXplaWQ9OSZ0bGRJZD00OTc2OTA4OCZjYW1wYWlnbklkPTEyNjcxJmNyZWF0aXZlSWQ9MCZ1Y3JpZD0xOTAzODY0ODc3ODU2NDc1OTgwJmFkU2VydmVySWQ9MjQzJmltcGlkPTU0MjgyODhFLTYwRjktNDhDMC1BRDZELTJFRjM0M0E0RjI3NCZtb2JmbGFnPTImbW9kZWxpZD0yODY2Jm9zaWQ9MTIyJmNhcnJpZXJpZD0xMDQmcGFzc2JhY2s9MA==_url=https://lrtt.lt/

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.bg/url?q=https://lrtt.lt/

http://211-75-39-211.hinet-ip.hinet.net/Adredir.asp?url=https://lrtt.lt/

http://clients1.google.bg/url?q=https://lrtt.lt/

http://ads2.figures.com/Ads3/www/delivery/ck.php?ct=1&oaparams=2__bannerid=282__zoneid=248__cb=da025c17ff__oadest=https%3a%2f%2flrtt.lt

http://clients1.google.gy/url?q=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt

http://clients1.google.com.ar/url?q=https%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt

http://com.co.de/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=lrtt.lt

http://clients1.google.com.jm/url?q=https://lrtt.lt/

http://home.speedbit.com/r.aspx?u=https://lrtt.lt/

http://cse.google.com.lb/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt%2F

http://blog.bg/results.php?q=%22%2f%3e%3ca+href%3d%22http%3a%2f%2flrtt.lt&

http://images.google.com.co/url?sa=t&url=http%3A%2F%2Flrtt.lt%2F